Photographs are constructs that give the illusion of documentation. Early photographic processes like cyanotype were invented specifically to produce images that were faithful reproductions of people and places. Hand-coloring of monochrome images evolved in tandem with early photography to enhance this realistic effect. Photographs have essentially been used as evidence to prove a certain reality. But at each step of the process, the photographer manipulates light and shadow, and decides what to include in the frame and what to selectively omit. What results is a subjective impression of the real.

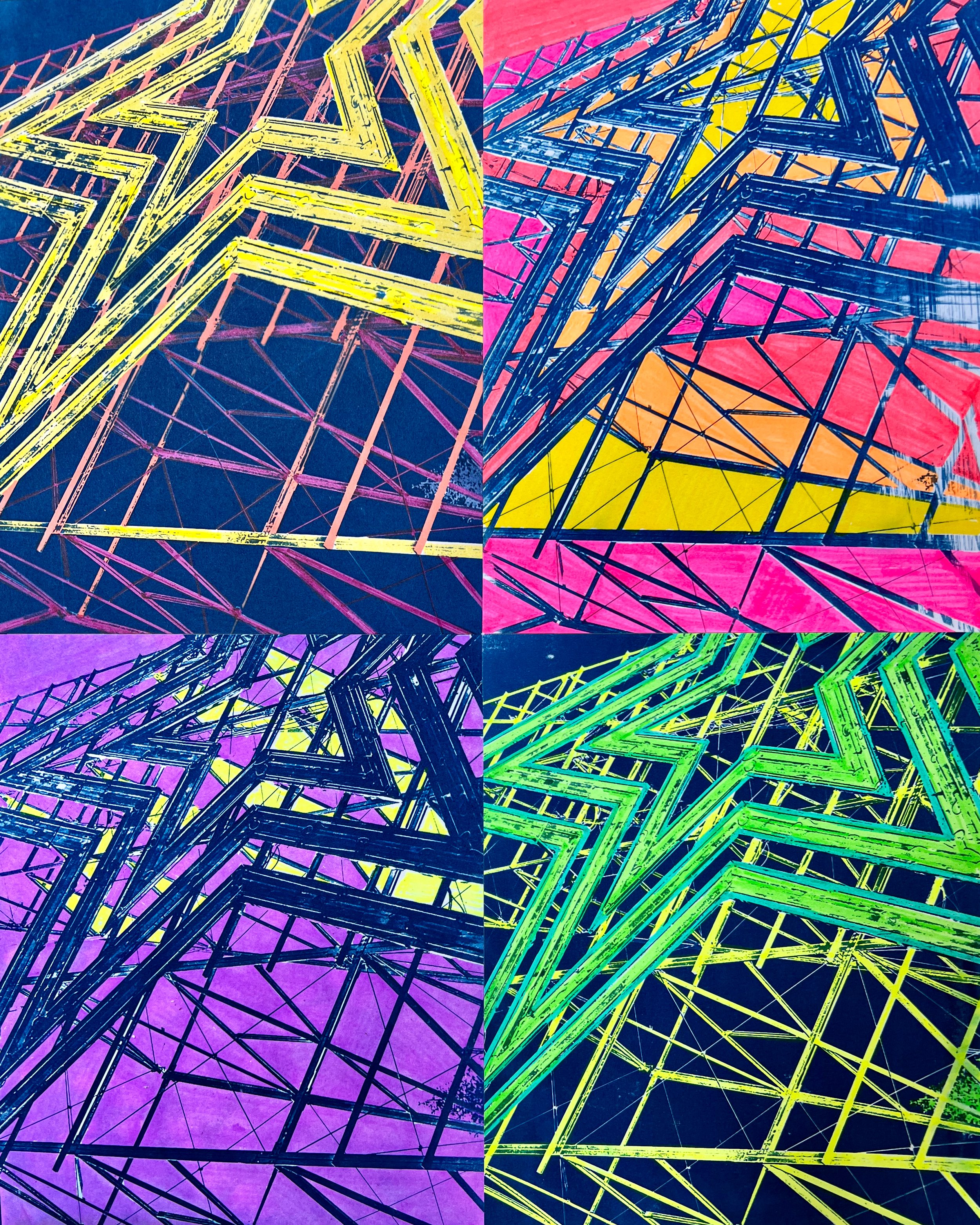

The COLOR STUDIES series of images uses traditional cyanotypes that are hand-colored with highlighter pens- everyday office supplies. Highlighters are designed to call attention to something to be remembered. The color directs the viewers’ attention to certain areas of the image, whether it is the foreground, the background, or the spaces in between. Here manipulation of the image is not subtle as in traditional hand-coloring of photographs.

The initial choice of highlighter was random. Driven by a desire to add color to the cyanotype, disappointed with the dull muddy images produced by toning cyanotypes and faced with a limited selection of materials, I tried fluorescent color and loved the result. Highlighters have unique properties. The neon, transparent color allows the image beneath to show through. It seeps into the paper, whereas paint, no matter how translucent, sits on top.

From an archival standpoint, neon colors in general and highlighters in particular, are fugitive colors, pigments that are less permanent when exposed to environmental factors. Using color that is essentially temporary is intentional. This work leans into he notion of impermanence. The photos were created spontaneously in a spirit of play. The images were chosen at random for this series, simply because they might be interesting with the addition of color. It’s not about what the images represent so much as it is about the bold color and graphic nature of the resulting image. Colors were chosen purposefully to be unnatural-maybe a little lurid, a little ominous, artificial.

Much of my work as a whole deals with the idea of what remains, but permanence is not necessarily an indication of quality or of value. What endures is largely a result of chance. Mundane things get kept, passed on, and precious things (and people) are lost forever. Who decides what is ‘worthy ‘of preservation? COLOR STUDIES are intentionally ephemeral; there is no pretense that they are archival. They are impermanent, like everything. Life has shown us starkly in the last few years- climate change, pandemic, war, shootings- that we can lose who/what we value at any time. The bright intensity of color, the attention to the construction of the image, and the fleeting quality of the materials in this series acknowledges temporality and celebrates the now.

“We All Shine On” cyanotype and highlighter, 16 x 20 inches